18TH AND 19TH CENTURIES OTTOMAN IMPERIAL MOSQUES

They were often designed as monumental complexes that included multiple structures. These mosques are not only architecturally significant, but also central to the city’s artistic and cultural patrimony.

While many were grand and monumental, some were smaller, reflecting the stylistic trends of their respective eras.

In my previous post, I wrote about the 16th and 17th centuries imperial mosques. This post turns to a later period, the Ottoman imperial mosques of the 18th and 19th centuries. The list is by no means comprehensive. Almost every sultan, and even members of the dynasty, sought to leave their mark on the city.

YENI VALIDE MOSQUE (1711)

Located in Üsküdar, on the Asian side of Istanbul, the Yeni Valide Mosque was commissioned by Sultan Ahmed III in honour of his mother, Emetullah Râbi’a Gülnûş Sultan.

Completed in 1711, it formed part of a larger complex that included a hospice, an arasta (a marketplace whose income supported the mosque’s maintenance), a primary school, a fountain and even a clock tower.

Architecturally, the mosque remains faithful to the classical Ottoman style associated with Mimar Sinan. In fact, it is a close replica of the Rüstem Pasha Mosque.

It also represents one of the earliest examples of the emerging 18th-century preference for taller and narrower minarets.

Gülnuş Sultan, once the cherished Haseki of Sultan Mehmed IV, rose to even greater prominence as Valide Sultan when destiny placed both her sons, Mustafa II and Ahmed III, upon the Ottoman throne. As mother of two reigning sultans, she stood at the heart of the empire’s power and legacy.

NURUOSMANIYE MOSQUE (1755)

Prominently located near the entrance to the Grand Bazaar, the Nuruosmaniye Mosque is also one of the most recognizable landmarks of Istanbul.

Commissioned by Sultan Mahmud I in 1748 and completed under Sultan Osman III in 1755, it is a masterpiece of the Ottoman Baroque style. Its very name, “Light of Osman”, refers to Osman III. It alludes to the mosque’s unusually large windows, which flood the interior with light.

Its commanding presence on the skyline positions it alongside other iconic monuments such as Hagia Sophia, the Süleymaniye Mosque, the Yeni Mosque and Topkapı Palace.

AYAZMA MOSQUE (1760)

Commissioned by Sultan Mustafa III in memory of his mother, Mihrişah Kadın, the Ayazma Mosque is often described as a smaller version of the Nuruosmaniye Mosque. Completed in 1761, it demonstrates how the Nuruosmaniye’s design became a model for later imperial foundations.

Although less monumental in scale, the Ayazma reflects the same Baroque style of ornament, curved façades and bright interiors. Its reduced proportions suggest a shift from the massive complexes of the classical era to more intimate religious structures.

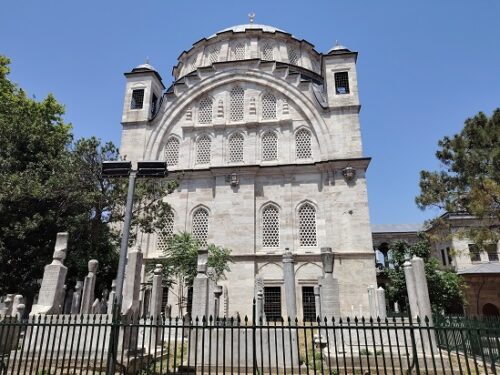

FATIH MOSQUE (1771)

The original Fatih Mosque, commissioned by Fatih Sultan Mehmed only a decade after his conquest of Constantinople, was completed in 1470. It was the second major imperial complex constructed in the city. Also, it played a foundational role in establishing the Ottoman architectural presence in the former Byzantine capital.

However, the structure was destroyed in the devastating earthquake of 1766. Sultan Mustafa III subsequently commissioned a complete reconstruction in 1771, this time in the Ottoman Baroque style. Although the present structure differs markedly from the original, it remains one of the most imposing mosques in Istanbul.

LALELI MOSQUE (1783)

Completed in 1764, the Laleli Mosque was another of Mustafa III’s commissions. Destroyed by fire in 1783, it was rebuilt almost immediately. The mosque exemplifies the late 18th-century Ottoman Baroque, with elegant curves and a richly decorated interior.

Although subsequent disasters, including the fire of 1911 and the urban renewal projects of the early 20th century, erased much of its original külliye, the mosque itself survives as one of the jewels of the late Ottoman capital.

EYÜP SULTAN MOSQUE (1800)

The Eyüp Sultan Mosque occupies a unique place in Ottoman religious and political culture. Constructed initially by Fatih Sultan Mehmed shortly after the conquest, it was built on the site where Abu Ayyub al-Ansari, the companion and standard-bearer of the Prophet Muhammad, died during the first Arab siege of the city in the 670s.

The mosque became the ceremonial site of enthronement. Each new sultan was girded with the Sword of Osman there, affirming his legitimacy.

By the late 18th century, however, the mosque had fallen into ruin. Sultan Selim III ordered its complete reconstruction in 1800.

GRAND SELIMIYE MOSQUE (1805)

Built in Üsküdar near the Selimiye Barracks, the Grand Selimiye Mosque was completed in 1805 under Sultan Selim III. The mosque’s scale, monumental dome and association with the nearby barracks emphasize its close relationship with the military reforms of the era.

Its külliye included schools, fountains and a hammam. Although the surrounding neighborhood has modernized, the mosque remains one of the most important examples of early 19th-century Ottoman Baroque. It demonstrates how imperial mosques continued to serve as instruments of both religious devotion and political symbolism during a period of reform.

NUSRETIYE MOSQUE (1826)

Commissioned by Mahmud II, the Nusretiye Mosque was completed in 1826 to commemorate his decisive victory over the Janissaries, whose corps he abolished that same year. Located in Tophane, it was one of the last great mosques built in the Ottoman Baroque style.

The mosque stands as a political statement. Its very name, “Nusretiye” (Victory), immortalizes Mahmud II’s success in consolidating power and modernizing the empire.

In this way, imperial mosques continued to function as both architectural and ideological instruments of the state.

TEŞVIKIYE MOSQUE (1854)

Started under Selim III in 1794 and completed under Abdülmecid I in 1854, the Teşvikiye Mosque represents a marked departure from earlier Ottoman religious architecture. Its Neo-Baroque style, with its white-columned façade and pronounced European features, signals the increasing incorporation of Western architectural forms into the Ottoman repertoire.

Located in Şişli, the mosque reflects the changing social geography of 19th-century Istanbul. New neighbourhoods beyond the traditional core of the city became sites for imperial patronage

DOLMABAHÇE MOSQUE (1855)

Bezmialem Valide Sultan initiated the construction of the Dolmabahçe Mosque, which was completed by her son, Sultan Abdülmecid I, in 1855.

Its location, directly on the Bosporus and adjacent to the Dolmabahçe Palace, rendered it the official palace mosque. Combining European stylistic influences with Ottoman elements, it is among the most iconic Ottoman imperial mosques of the 19th century.

SULTAN MUSTAFA ISKELE MOSQUE (1858)

First built by Sultan Mustafa III in 1761, the Iskele Mosque in Kadıköy was destroyed by fire in 1858 and subsequently rebuilt in brick under Abdülmecid I.

Although more modest than many other imperial foundations, it demonstrates the persistence of dynastic patronage even in suburban districts.

PERTEVNIYAL VALIDE SULTAN MOSQUE (1871)

One of the last imperial mosques built in Istanbul, the Pertevniyal Valide Sultan Mosque (1871) exemplifies the eclectic spirit of the late Ottoman period. Its design fuses Ottoman Rococo with Gothic, Renaissance and Empire elements, creating a richly ornamental and highly Europeanized structure.

Commissioned by Pertevniyal Sultan, wife of Mahmud II and mother of Abdülaziz, the mosque reflects the continuing role of royal women as patrons of religious architecture.

With its elaborate decoration and unusual stylistic mix, it represents both the culmination and transformation of the imperial mosque tradition in Istanbul.

The imperial mosques of the 18th and 19th centuries illustrate both continuity and transformation in Ottoman architectural history. While retaining their role as symbols of sovereignty, dynastic memory and urban order, they absorbed new stylistic influences from Europe, most notably Baroque, Rococo and Neo-Baroque elements.

These mosques testify to the adaptability of Ottoman architecture and the ongoing significance of religious monuments as instruments of imperial self-representation.

I hope that this and my earlier post will encourage those interested in Ottoman history to explore these magnificent monuments. In future posts, I will look at each of these mosques in greater detail.

Back to Turkey